Planning Appeal & Veteran Trees – Tree Frontiers Review

In January 2024, The Biodiversity Gain Requirements (Irreplaceable Habitat) Regulations 2024 (BGR) provided us with the first legal definition of a veteran tree. This built upon previous guidance offered in the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) and its supporting Planning Policy Guidance (PPG). There is insufficient space here to provide the detail of what the various definitions are, but in summary, BGR says that for a tree to be considered to be a veteran, it must exhibit “one or more” of defined features such as significant decay, large girth, or high value for nature. This has caused some debate within the sector, as on the face of things this tight definition goes against the previous (and long term) consensus that veteran trees are those with an accumulation of features that are valuable for nature. The assessment of a veteran tree is a complex and subjective matter that cannot be neatly tied up in a few sentences.

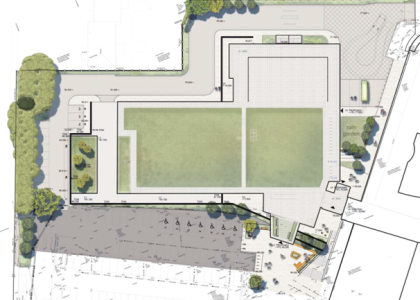

The situation has recently come to a head in a planning appeal for a development site near Bolton (APP/N4205/W/25/3365804). At the crux of the appeal was a debate around whether the scheme would have an impact on several trees that had been classified as veterans, with the classification relying heavily on the fact that the trees were recorded as veterans on The Woodland Trust Ancient Tree Inventory (ATI). Again, space limits the option to cover the detail of the issues reviewed in the appeal, but there were two significant outcomes.

The first is that there are differences in the definitions of a veteran tree between BGR, NPPF and PPG which (to quote from the appeal) “leads to a degree of uncertainty for planning purposes”. In order to address this, the inspector concluded that while there were also areas of commonality between the various definitions, there must also be acknowledgement that “different species and individual trees have different life spans and grow at different rates” and this can add to the complexity of determining when a veteran is a veteran.

The inspector also referenced an earlier appeal from 2023 where that inspector “concluded that a veteran tree must have multiple veteran characteristics in order to have exceptional biodiversity value, which they found was the only relevant criteria for the trees.” Interestingly, there is a detailed discussion in the appeal in reference to the fact that the arboriculturist felt that the trees defined as being veteran in the ATI were in fact not veteran by virtue of the size but acknowledged that the tree might have some ecological value.

A botanist was then engaged to make the ecological assessment, and their conclusions was that none of the trees “have significant decay features, a large girth or a high value for nature and do not meet the BGR veteran tree definition”. Notwithstanding this, the inspector felt that these conclusions were insufficient in weight when balanced against the inclusion of the trees on the ATI.

The inspector also concluded that “even if it had been robustly demonstrated that the ATI veteran trees do not meet the strict definition in the BGR, nevertheless they appear to meet the PPG veteran definition in relation to life stage and condition”.